Assessments are an integral part of learning. The testing process is not merely evaluative, but formative; the exercise of recall and critical application, supplemented by curated feedback, strongly reinforces understanding. Good quiz design makes for better students – a well-written question aims beyond superficial examination of knowledge and intends to serve a candidate long after the conclusion of their course.

The Multiple-Choice Question (MCQ) format is the most widely used type of assessment worldwide. This is likely primarily because MCQs are easy to administer and mark. However, MCQs are often criticized for having substandard design. This is partly due to poor implementation – MCQs are frequently used to evaluate trivial concepts – but equally because an essential aspect of MCQ question design is commonly overlooked: distractors.

What Makes a Bad Distractor?

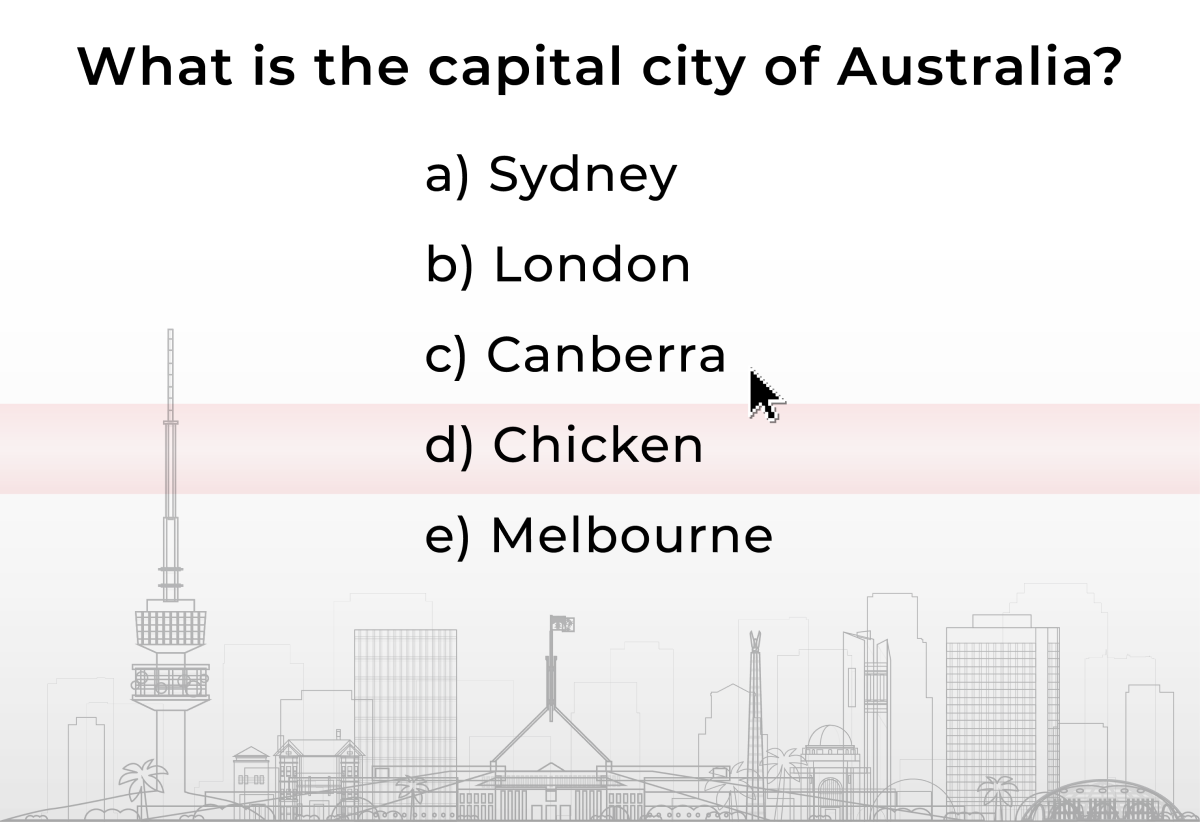

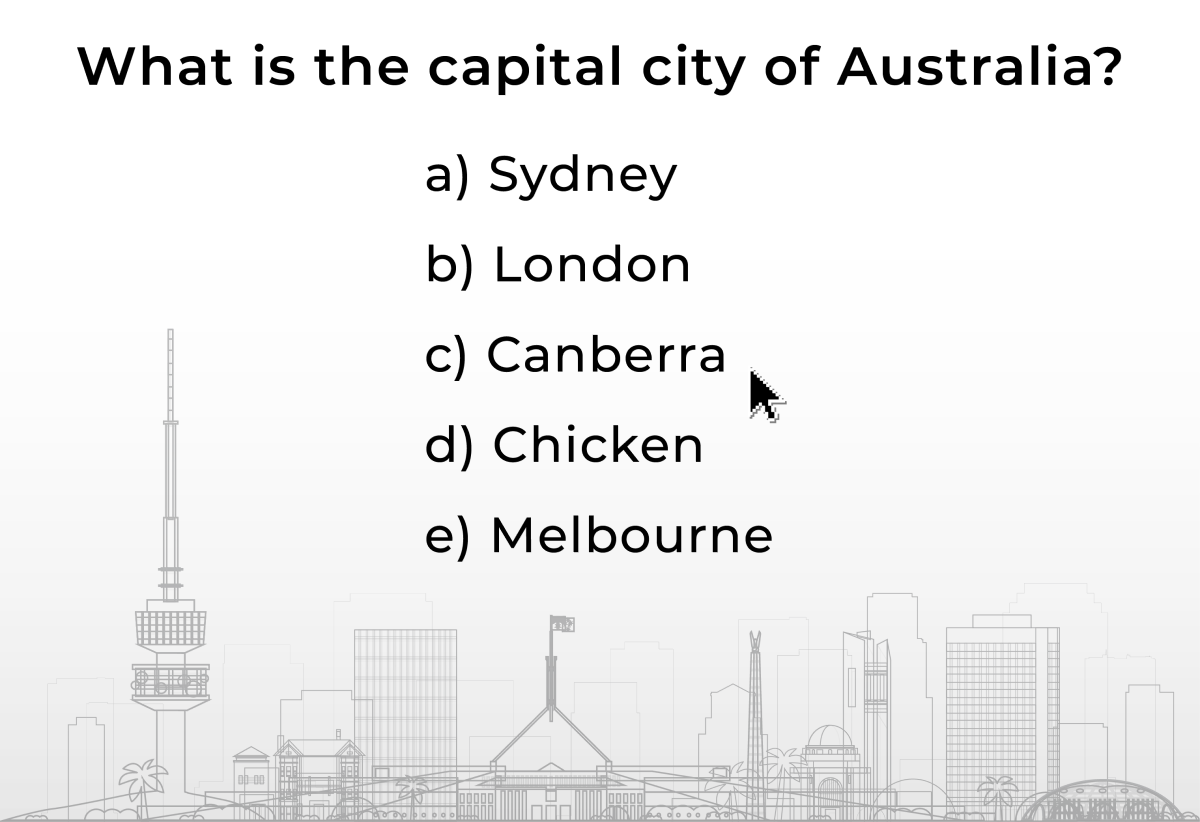

Distractors are the incorrect answers in a Multiple-Choice Question. They serve an invaluable function within question design: creating context. In order to understand how to create a good distractor, it is important to recognise and avoid common pitfalls that lead to poor ones. A poor distractor completely undermines the integrity of the question. Consider the following example:

Answer d) above is an example of an ostensibly poor distractor. It is reasonable to think that, assuming this question supplements a well-designed course, students will identify that “chicken” is incongruous in this context. By instantly ruling out a distractor, students have a higher chance of selecting the correct answer – even if they guess. In part, this process has turned the MCQ from a fair evaluation of knowledge into a logic meta-game.

This occurs frequently, even when using stereotypical distractors. For example, “all of the above” or “none of the above” are equally susceptible: if a candidate can confidently rule out even one distractor, they can simultaneously do the same for an “all of the above” option – further increasing their chances of guessing the right answer. Consequently, designers should avoid any phrasing or structure that could provide hints to students: for example, absolute terms (“always”, “never”); distractor length (correct answers are often more detailed or complete than distractors); and both grammatical and logical cues.

What Makes a Good Distractor?

Each of the above examples of poor distractors have something in common: in some way, their presence in the question undermines its integrity. Above all, a question must be fair to the candidate. A good question is clear and pure, with the intention of evaluating a student’s understanding of only relevant information, and nothing extraneous.

Therefore, distractors should generally follow this golden rule:

"A good distractor appears plausible but is necessarily incorrect"

The premise underpinning this rule is the notion that only students who wholeheartedly understand a topic will be able to confidently answer a question. A student who does not know the course content will not receive any advantage in guessing, since all answers seem indistinguishably plausible. However, a student that deeply understands the content should be able to identify that only one answer is actually true. Therefore, it is important for a designer to conduct appropriate due diligence to ensure that only one answer is correct, and that all other answers cannot be correct under any circumstances.

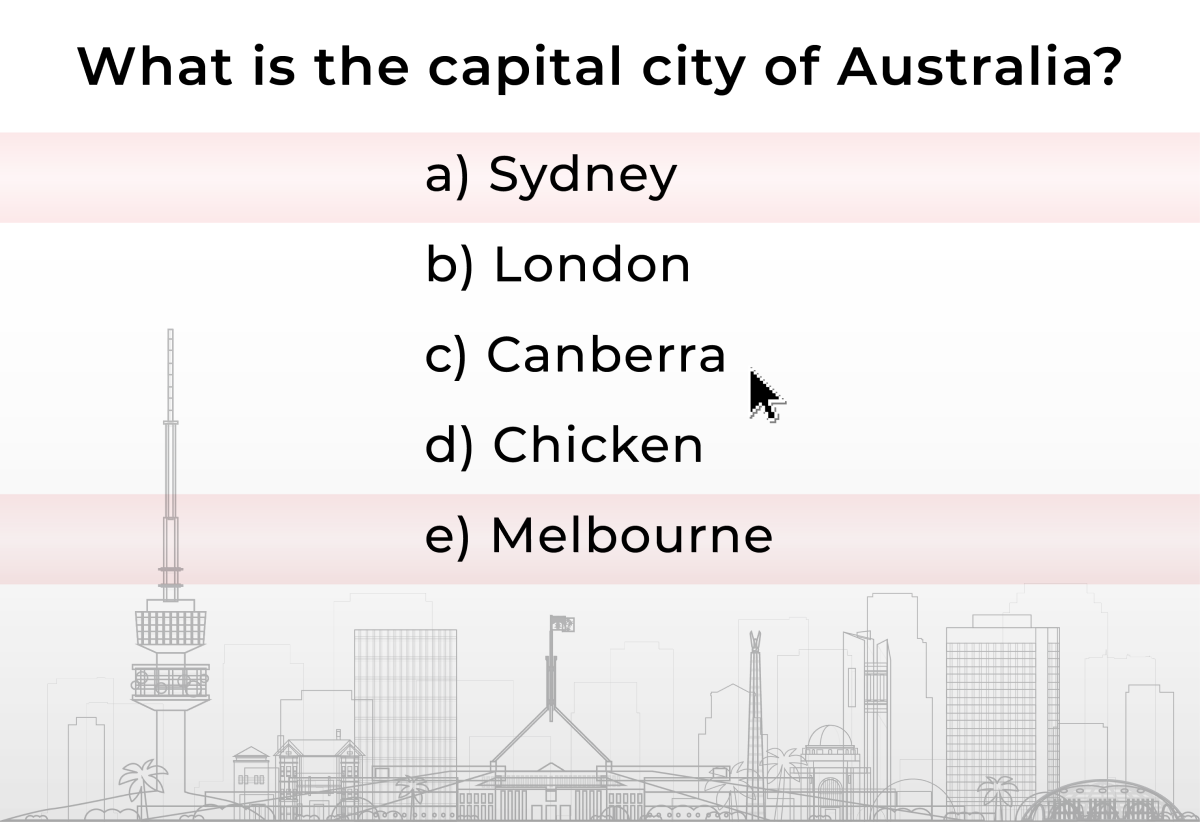

Returning to the previous example:

Answers a) and e) are examples of typically good distractors. It is common for non-Australians to assume that either Sydney or Melbourne is the capital of Australia; usually because they know the cities are the biggest within the country, or that they are cultural and economic hubs. Thus, they “appear plausible” to those who do not confidently know the answer. However, they are also “necessarily incorrect”: it is indisputable that answer c) – Canberra – is the capital of Australia.

Moreover, the reason these are good distractors lies beyond the fact that they follow the golden rule. Distractors a) and e) afford the examiner the opportunity to provide curated feedback that may not only reinforce the candidate’s knowledge, but also provide additional relevant exposition surpassing the scope of the course. For example, if presented with feedback that discusses why both Sydney and Melbourne are incorrect answers – that is, the historical context of the dispute between the two cities over which should be the national capital, and how Canberra was chosen instead as a compromise – the candidate will be far more likely to recall the correct answer, as well as gaining supplementary knowledge that enriches their understanding of the topic beyond the superficial intent of the question. Feedback, when implemented in this way, is a powerful learning tool – a good distractor will often be curated precisely for the purpose of providing relevant feedback.

Coming Full Circle

Ultimately, however, there are no strict rules to quiz design – only guidelines. Above all else, it is important to recognise that context and fairness to the candidate are paramount. Returning to our example a final time:

An assessment and its context are inextricably intertwined – the quality of this question (and its distractors) cannot be determined in a vacuum. While distractor d) is the most obvious outlier, one could argue that b) is almost as poor, since it is common knowledge that London is not an Australian city. However, it might be justifiable to include b) if this question was posed to a first-grader – for this demographic, it can no longer be implicitly assumed common knowledge; instead, it could satisfy the criterion of “appearing plausible”. Taking it a step further: if this question was presented in a course for graduate-level students specialising in Australian geography, the question itself would be trivial and redundant.

Furthermore, for a first-grader, would d) really be a poor distractor? A significant element of education is maintaining a student’s attention; children would easily identify it as being silly, and a savvy teacher in a classroom discussion environment could use their recaptured interest as an opportunity to segue into further reinforcing Australian geography. Nevertheless, it would be clearly inappropriate to include this distractor in a university end-of-term assessment.

To reiterate: only context and fairness matter in question design.

Understanding the environment in which a question is posed is just as important as understanding its goal. With our repeated example, we have demonstrated that any – or none – of the above distractors are valid under different conditions. There are no categorical truths to designing a good distractor (or a good question); just general principles that can be dismissed under appropriate circumstances. Each individual case has its own nuance, and it is ultimately up to the designer to judge how to create a distractor such that it best benefits the student.